Turkey’s shift away from the Western power structures and towards Russia has been a theme for a number of years, with Ankara likely feeling snubbed by a European Union dragging its feet over membership.

Once bitten, twice shy, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan instead embraced the traditional counterbalance to Nato in a Russia resurgent due to its near limitless fossil fuel supply and extensive network of influence in Europe.

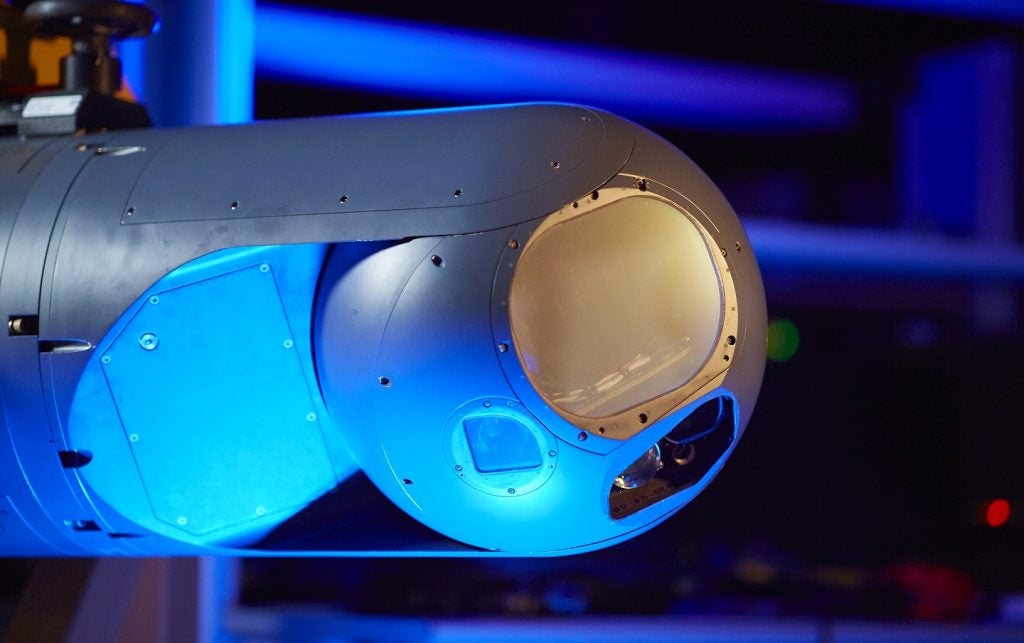

A key schism between Turkey and the West came when Ankara in the late 2010s sought to acquire the S-400 ground-based air defence system from Russia, a sophisticated high-altitude interceptor capability designed to target the latest US and European fighters. Turkey, at this time, was a leading partner in the US-led F-35 fifth generation stealth fighter programme, looking set to acquire significant numbers of aircraft and also bring benefit to its burgeoning aerospace sector.

However, the US saw a problem with Turkey acquiring both the Russian S-400 and the F-35, fearing that secretive technologies could fall into the wrong hands, and present Moscow with a way to break the code and defeat the aircraft’s stealth capability. Considering the length to which the US and Nato allies have gone to in recovering crashed F-35 aircraft in the Indo-Pacific and Mediterranean in recent years, and it is clear the Western alliance is set on preventing Russia or China from gaining any access to its technology.

Due to its acquisition of the S-400 Turkey was unceremoniously kicked out of the F-35 programme, causing a significant diplomatic storm, no little embarrassment, and leaving Erdoğan with little option but to double down with Russia.

Can Turkey gain re-entry to the F-35 programme?

However, might there be, if Erdoğan is removed from power, a way back for Turkey into the F-35 programme? Even if that were the case, would Turkey feel the need to, given its investment in its own aerospace sector and the development of the indigenous TF-X fighter?

James Marques, aerospace and defence analyst at GlobalData, said the “possibility is there”, but that if Turkey would be given the opportunity to join the F-35 programme it would have to be done so as part of “a broader reassessment” of the country’s whole defence-industrial strategy.

“The programme would bring a lot of economic benefits at a time where Turkey is struggling, and a new deal could be symbolic of resetting fraught relations with the West. But it isn't as straightforward as it seems, the US will likely want something in return. The current Turkish defence minister insists all they want is a refund for the money they already put into the F-35, but this could just be bluster and he may be gone entirely soon,” Marques explained.

The single biggest hurdle to Turkey’s re-entry into the F-35 programme, according to Marques, would be the S-400 missile system acquired from Russia in 2019 which was, as earlier stated, the reason for its dismissal.

“The US has been trying to gain access to these systems both for their intelligence and possible donation to Ukraine - but they will also probably never give Turkey F-35s whilst they have the 400,” said Marques, with even the prospect of those two competing technologies in the same military seen as too much of an intelligence risk.

Another factor is Turkey’s diplomatic role as a go-between for Russia and the West, with Ankara donating equipment to Ukraine and also being “a third party” in what few talks have been held in the now near three-year-old war, while also previously being a guarantor of the now defunct Black Sea Grain Initiative.

In addition, Russian contractors are working on a £20bn nuclear power plant in Turkey, an example of the extent of economic dependency between the two countries.

“Even if the new leader is more pro-Western, it would be difficult for them to upset the balance between looking east and west without headaches for themselves,” Marques said.

Regardless, Turkey will continue to invest in domestic defence projects in the long-term but have also shown a willingness to purchase combinations of foreign equipment while developing their own capabilities.

According to Marques, Turkey’s military favours an investment strategy in a mixture of new equipment while also upgrading older systems, described as the “high-low” mix, which sees high-end platforms used to counter the larger threats and more affordable equipment for smaller and everyday tasks.

“You can see this in their current jet fleet with both old F-4s and newer F-16s as well as the Army's tanks. The TF-X is currently unproven, and costs may run too high, especially with the bad economic situation. A new government may also change things. But Turkey is often willing to mix foreign and homegrown kit,” Marques detailed.

Time will tell whether Turkey will ever find itself in a position to once again be trusted by the US with capabilities reserved only for the closest of allies, a peculiar turn of event given both are Nato partners.

[Edit note 30.1.2024: This story was originally published prior to the 2023 elections in Turkey, and has since been amended and updated]