The UK House of Commons Defence Committee has published a report decrying the country’s Indo-Pacific strategy on 24 October.

In 2021, the British Government committed to engage more deeply in the Indo-Pacific – a region it recognizes as a “global centre of strategic activity”. Britain began to strengthen its ties with countries that subscribe to a free and open Indo-Pacific region, which has become a focus of contention with China’s aggressive military posture and North Korea’s provocative nuclear missile threats.

Seven months ago, in the Integrated Review Refresh, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak declared that the UK has delivered the ambition of a greater Indo-Pacific presence.

The Government suggested it had achieved the tilt, “largely through non-military instruments – such as diplomacy, trade, development, technological exchange and engagement with regional organisations – accompanied by a modest initial increase in our regional defence presence.”

Despite these efforts, the Defence Committee does not share the same sentiment. Rather, their findings indicate

“With only a modest presence compared to allies, little to no fighting force in the region, and little by way of regular activity, UK Defence’s tilt to the Indo-Pacific is far from being achieved.”

Building the UK’s regional presence

The UK has responded to the escalating tensions in the Indo-Pacific by increasing military deployments to the region, such as its Littoral Response Group (LRG).

Since 2022, the offshore patrol vessel HMS Spey rapidly delivered crucial humanitarian aid to Tonga in January 2022, following an underwater volcanic eruption and tsunami.

Moreover, its sister vessel, HMS Tamar, carried out patrols to ensure the enforcement of United Nations sanctions against North Korea, thereby contributing to the rules-based international order.

According to the UK Ministry of Defence, the deployment of the LRG will “build on the achievements of the Carrier Strike Group [sent to the region in 2021, but has since returned] by demonstrating enduring UK interest and presence in the region”.

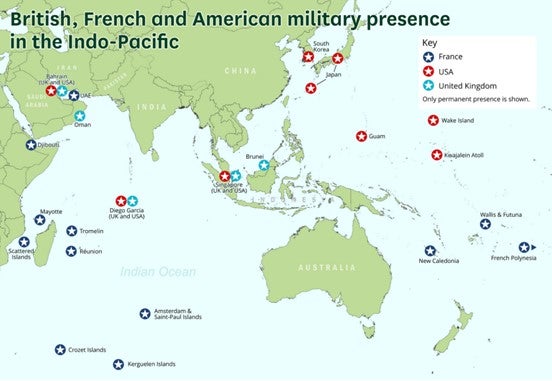

The Defence Committee compares this form of presence with that of the US and France.

“The UK’s regional military presence in the Indo-Pacific remains limited and the strategy to which it contributes is unclear.

“This contrasts to both the US—a global and Pacific power—and to France–a more comparable actor to the UK in terms of geography, scale, and military capability.

“Without a larger permanent presence, it is unlikely that the UK would be able to make a substantial contribution to allied efforts in the event of conflict in the region.

“In order to deliver this, the Government must make a choice as to whether it will increase resources in the region or rebalance current resources towards the Indo-Pacific.”

Assessing priority engagement in the region

The latest British military venture to the region came last week, when UK Armed Forces participated in a three-week exercise in Malaysia, where these services jointly operated with Malaysia, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand.

While this show of military interoperability appears to represent a step in the right direction – much in line with the Government’s admiring, yet ambiguous rhetoric – Britain already has a relatively strong partnership with these four Indo-Pacific nations.

While it is useful for the UK to point to its relationships with these nations, the Defence Committee suggests that the UK’s relationship with other countries such as Japan and India are particularly strategic, and little has been achieved here.

“As Japan enhances its own defence posture,” whose budget GlobalData intelligence projects will grow up to $85.9bn by 2028, “the UK should build on these valuable commitments to continue strengthening UK–Japan defence co-operation and remain steadfast allies in the pursuit of a free and open Indo-Pacific region,” the Defence Committee claims.

“The UK should plan a programme of joint exercises with the Japanese Armed Forces and continue collaboration on science and technology programmes as part of the Hiroshima Accord.”

Similarly, the Committee adds that the UK ought to make headway with India to encourage the subcontinent to decouple from Russia.

“The Government should work to establish the UK as a top tier defence partner to India through greater government-to-government co-ordination, and by creating strategic industrial partnerships to provide greater opportunities for the UK defence industry. This should include supporting efforts by India to reduce its dependency on Russian military equipment.”