A recent flurry of activity in India’s defence industry marks an escalation in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s atmanirbhar strategy, analysts say, which aims to bolster indigenous arms production and reduce reliance on Russian, French, US and Israeli imports.

Earlier today (1 March), India's Ministry of Defence (MoD) signed Rs195.2bn ($2.36bn) in contracts to procure nuclear-capable BrahMos missiles for the navy.

This follows the inauguration of two new weapons factories in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh on Monday (26 February), at which Adani Defence and Aerospace announced further plans to invest Rs30bn ($362.1m) into domestic arms manufacturing and build a vast defence complex in Mumbai.

Adani also launched India’s first intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance drone last month in a joint venture with Israel’s Elbit Systems.

Nevertheless, India remains the world’s biggest importer of arms from overseas, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIRPI), despite the country’s arms imports declining by 11% between 2018 and 2022.

These events are a bellwether for “the cost of Indian-produced weapons to decrease substantially … over the next few years,” says Abhijit Apsingikar, Senior Defence Analyst at GlobalData.

India seeks atmanirbhar defence industry

India’s push towards military autonomy is fuelled by geopolitical tensions with long-time rivals China and Pakistan.

There have been frequent skirmishes between Indian and Chinese troops along their shared – and disputed – 3,440km border, while India and Pakistan continue to struggle for control over the Kashmir region.

“India has a very high threat perception,” Apsingikar tells Army Technology. “It is bound by two hostile states along its northeastern and northwestern borders, which compels it to maintain a large standing army.”

Geopolitical tensions have also compelled Modi to accelerate his policy of ‘atmanirbhar Bharat’, or ‘self-reliant India’, in the defence industry – as well as in rail, construction and medical devices.

“Traditionally, the Russian Federation has been the single largest supplier of weapons to India,” Apsingikar adds. “Most of the weapons systems in the Indian military arsenal are of Russian origin and will likely remain so for at least the next few years.”

But India is already facing difficulties with its main arms supplier.

“It is likely that the invasion of Ukraine will further limit Russia’s arms exports,” says Siemon Wezeman, Senior Researcher with the SIPRI Arms Transfers Programme. “This is because Russia will prioritise supplying its armed forces and demand from other states will remain low due to trade sanctions on Russia and increasing pressure from the USA and its allies not to buy Russian arms.”

After Russia, France is India’s leading arms supplier, with New Delhi buying up 30% of France’s weapons exports between 2018 and 2022. The US and Israel are India’s third and fourth biggest arms suppliers.

India has made its aim of defence self-reliance public.

In May, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh said Modi was “committed towards indigenisation”, even if efforts have so far resulted in persistent delays and rescheduling of delivery deadlines.

Apsingikar pinpoints foreign direct investment (FDI) as a key factor.

By “encouraging the Indian private sector to enter into joint ventures and partnerships with foreign OEMs and produce defence equipment domestically”, Modi aims to “make India relatively self-sufficient in defence production to negate the need to import expensive defence equipment”, he says.

Another Adani monopoly?

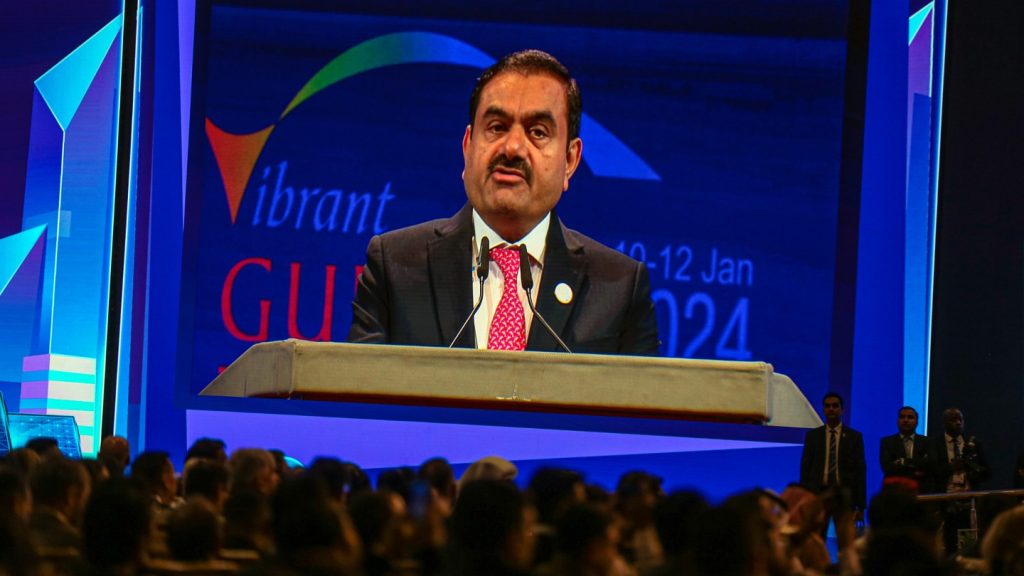

In pursuing atmanirbhar and innovative FDI, Modi will look to capitalise on a long-standing friendship with industrialist billionaire Gautam Adani, owner of the Adani Group.

Exemplified by the Elbit drone project, Adani has long-established business ties with Israel, where the conglomerate’s ports arm operates the Port of Haifa, Israel’s second largest.

Adani’s rise to become India’s wealthiest man has been concurrent with – and arguably co-dependent on – Modi’s rise to the pinnacle of Indian politics.

Both men come from the western state of Gujarat, and Adani has been a key supporter of Modi’s dominant Bharatiya Janata party which took power in 2014.

Despite accusations of stock manipulation and accounting fraud, Adani has generated billions in revenue through ventures in ports, electricity, natural gas, food and other areas.

His conglomerate’s defence arm has also been awarded favourable terms on manufacturing contracts by Modi’s government.

These look to be highly lucrative. India is set to invest $12.8bn in UAVs over the next decade, according to GlobalData’s Military UAV Market Size and Trend Analysis (2022-32) report with a substantial 70.4% allocated for the medium altitude, long endurance segment.

Adani and other commercial players are now challenging the decades-long status quo of government-owned companies like Advanced Weapons and Equipment India Limited (AWE) and Munitions India Limited (MIL) dominating India’s defence industry – and struggling to improve it.

Aside from Adani, TATA, Bharat Forge, Mahindra, and L&T are among the manufacturing conglomerates to follow Modi’s calls to indigenise India’s defence industry.

None are arms production specialists. The other four have some background in engineering, but Adani has traditionally been associated with operating the largest Mundra port in India.

This has been levelled as a criticism of India’s domestic defence industry, even if a similar landscape exists in Japan, where Kawasaki and Mitsubishi construct navy vessels, aircraft and missile defence systems as well as automobiles.

But having only entered weapons manufacturing in 2018, will Adani be able to monopolise an atmanirbhar Indiandefence industry?

Adani’s three new defence factories and promise of mass investment signal the billionaire’s intentions.

Indian Army Chief Manoj Pande inaugurated two new Adani defence facilities for the manufacturing of ammunition and missiles on Monday (26 February), before Adani announced plans for the new defence complex in Mumbai.

Adani and India's MoD did not respond when approached for comment by Army Technology.

Adani says it will manufacture a “full spectrum of ammunition” for India’s armed forces at the facilities, creating more than 4,000 jobs.

“Adani's munition factory is one of the largest in the world, capable of producing as many as 150 million small-calibre ammunition and supplying as much as 25% of Indian Armed Forces requirements,” Apsingikar concludes. “It would greatly expand the volume of production of weapons that are domestically produced in India.”

All signs indicate rapid, Adani-overseen expansion in India’s indigenous defence industry.

China and Pakistan will be among those watching closely as one of the world’s fastest-growing economies channels billions into self-armament.